Known for his ability to crack open coconuts using his powerful pliers to get to the edible kernel of the coconut. The palm crab is the largest terrestrial arthropod in the world. There are many names for this crab: coconut robber, palm thief, coconut crab, robber crab. Seen stealing shiny objects from houses and tents, such as pots or silver items. It can also climb a palm tree, cut off a nut, and when it falls to the ground, find it and eat it.

Appearance and dimensions

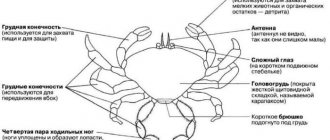

According to data from various sources, the size of the crab is: body length from 40 cm; weight 4.1 kg and leg span 93 cm. And they even saw a palm crab 14 kg and 1.8 m in body length. Males are usually larger than females. Life expectancy is from 30 to 60 years. Their body, like all arthropods, is divided into a front part (head and chest) with 10 legs and a butt.

The front pair of legs are powerful cutters capable of lifting objects weighing 29 kg, used for cracking coconuts. The next two pairs are large, powerful legs designed for movement and allowing crustaceans to climb trees to a height of 10 meters. The fourth pair of legs are smaller, resembling tweezers with forceps at the end. The last pair is very small and is designed to clean the respiratory system. These legs, as a rule, are hidden under the shell. There are some differences in color between animals living on different islands, ranging from light purple to brown.

Young individuals use snail shells to protect their soft bellies, and older individuals sometimes use coconut shells for this purpose. Like most common crabs, they tuck their limbs under their body to protect themselves. The change of shell lasts about 30 days, when the exoskeleton completely hardens, during which time the crab is helpless and hides from dangers in the hole.

Palm crabs cannot swim or dive; individuals drown in deep water. They use a special organ for breathing. This organ between the gills and lungs is one of the most valuable adaptations of these crabs to the environment in which they live. Consists of tissues similar to those that make up the gills, but absorbs oxygen from air rather than water. In addition, primitive gills also serve as an additional respiratory organ.

Another characteristic organ of palm trees is their nose. Like most arthropods living in water, they have special organs on their antennae that probe the direction of smell. Since these animals live on land, these organs have evolved to become something like the olfactory organs of insects. Palm thieves have an excellent sense of smell and are able to sense odors from a great distance. Particular attention is paid to the smell of decaying meat, bananas and coconuts, which they feed on.

Reproduction

Palm crabs mate frequently and quickly on land between May and September, and especially between early June and late August. Males and females wrestle with each other, with the male turning the female on her back for copulation, which lasts about 15 minutes. Males deposit sperm on the female's abdomen. The female's rear opens and fertilization occurs. Eggs are released on the ground, in crevices or burrows near the shore. Shortly after this, the females lay eggs and wear them on the underside of their abdomen, keeping the eggs under their body for several months. At hatching time, which is usually in October or November, the females release their eggs into the ocean at high tide.

The larvae swim in the ocean area along with other plankton for about a month, during which time many of them die from predators. After reaching the larval stage of development, snail shells of appropriate sizes settle on the bottom and along the edges. And they migrate towards the coastline along with other land hermits. Like all hermit crabs, they exchange shells in which they live when they grow. After a month, they leave the ocean and lose the ability to breathe in water. Young crabs who cannot find shells of the right size also use broken coconut shells. Five years after hatching, palm crabs reach sexual maturity.

Nutrition

The diet is based mainly on fruits, nuts or seeds. However, as omnivores, they also eat some organic foods, including leaves, rotten fruit, turtle eggs, carrion and the shells of other animals - probably to supply calcium. Palm crabs often steal food from each other and then retreat into their burrows to finish their meal in peace.

Palm crabs climb trees to eat coconuts and fruits, hide from the heat, or escape predators. Animals can use pincers to lift coconuts from the ground and strip them of their scales, and they can also climb to a height of ten meters and throw nuts from trees to the ground to get to their contents. This behavior is unique in the animal kingdom. Biologists believe that they are not smart enough to plan such actions and rather drop coconuts by accident when they try to open them on the tree.

Lifestyle

Palm crabs live alone, in underground burrows or rock crevices, depending on the sculpture of the area in which they live. They dig their holes in sand or loose soil. During the day they remain in the shade, protecting themselves from predators and from excessive water loss due to heat. When they rest in their burrows, they close the entrance with one of their forceps to create a humid microclimate suitable for the respiratory system. In areas where there are large populations of crabs, some crabs may leave the burrow during the day, probably to increase the chance of a bite. Palms live almost exclusively on land and can be found as far away as 6 miles from the ocean.

These arthropods live in the area from the Indian Ocean to the central Pacific Ocean. The largest and best preserved population is on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. Large concentrations of these mollusks are also found in the Bay of Bengal, in the Czagos archipelago. On these islands, crabs are protected from human hunting. Fines reach £1,500 per crab caught. In Mauritius and Rodrigues Island, these arthropods have become extinct.

Palm crabs are considered terrestrial arthropods - most aspects of their life are terrestrial. These crabs drown in sea water within just one day. Just like the fact that adult individuals cannot swim and can colonize new islands only during the larval period, when they can swim on water.

Status and protection

Palm populations may be decimated due to loss of natural habitats and human hunting. This species is protected by: IUCN Red Book of Invertebrates. However, according to the Red List of Threatened Species, scientists do not yet have sufficient data to classify the palm crab as an endangered species and therefore it is currently classified in the DD category “incomplete data”, provided that this assessment requires additions. Some regions have adopted conservation strategies with good results, such as Micronesia's ban on the harvesting of fertilized females.

Palm crab as a pet

Palm crab, when not yet fully mature, is also sold as a pet in Tokyo. The cage must be strong enough so that the arthropod does not break it with its pincers. If a crab grabs a person with its claws, it will not only cause pain, but it is also unlikely to let go on its own.

Crab is used as food by residents of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Its meat is considered an aphrodisiac, with a delicate taste reminiscent of lobster and other crab meat.

source

Interesting for you:

Origin of the species and description

Photo: Palm Thief

The palm thief is a decapod crayfish. The scientific description was first made by C. Linnaeus in 1767, when he received his specific name latro. But its original generic name Cancer was changed in 1816 by W. Leach. This is how Birgus latro, which has survived to this day, appeared.

The first arthropods appeared approximately 540 million years ago, when the Cambrian was just beginning. Unlike many other cases where, after emerging, a group of living organisms evolves slowly for a long time, and the diversity of species remains low, they became an example of “explosive evolution”.

Video: Palm thief

This is the name for the sharp development of a class, in which it gives rise to a very large number of forms and species in a short (by evolutionary standards) period of time. Arthropods immediately mastered the sea, fresh water, and land; crustaceans, which are a subtype of arthropods, also appeared. Compared to trilobites, arthropods underwent a number of changes:

- they acquired a second pair of antennae, which also became an organ of touch;

- the second limbs became shorter and stronger, they turned into mandibles intended for grinding food;

- the third and fourth pair of limbs, although they retained motor function, became also adapted for grasping food;

- the gills on the head limbs were lost;

- the functions of the head and chest were separated;

- Over time, the chest and abdomen emerged in the body.

All these changes were aimed at allowing the animal to move more actively to search for food, catch and process it better. The oldest crustaceans of the Cambrian period left many fossil remains, and at the same time higher crustaceans appeared, which include the palm thief.

Some crayfish of that time were already characterized by a modern type of nutrition, and in general the structure of their body cannot be called less perfect than that of modern species. Although the species that lived on the planet then became extinct, modern ones are similar in structure to them.

This makes it difficult to reconstruct the evolution of crustaceans: it is impossible to trace how they gradually became more complex over time. Therefore, it has not been reliably established when palm thieves appeared, but their evolutionary branch can be traced back hundreds of millions of years, all the way to the Cambrian.

Interesting fact: Among crustaceans, there are even those that can be considered living fossils - the shieldfish Triops cancriformis has lived on our planet for 205-210 million years.

Links[edit]

- ^ a b c d Cumberlidge, N. (2020). "Birgus latro" IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

.

2020

: e.T2811A126813586. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T2811A126813586.en. - Patsy McLaughlin (2010). P. McLaughlin (ed.). "Birgus latro (Linnaeus, 1767)". World Paguroidea Database

. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved March 3, 2011. - ^ abc Patsy A. McLaughlin; Tomoyuki Komai; Raphael Lemaitre; Dwi Listyo Rahayu (2010). Martin E.Yu. Short; Sh. Tan) (ed.). "Part I - Lithodoidea, Lomisoidea and Paguroidea (an annotated list of the anomuran decapod crustaceans of the world (exclusive from Kiwaoidea and the families Chirostylidae and Galatheidae of Galatheoidea" (PDF). Zootaxa

Suppl 23:... 5-107 Archived from the original (PDF) on 01/22/2012 . - Harries, H. C. (1983). "The Coconut Tree, the Robber Crab and Charles Darwin." Principles

.

27

(3): 131–137. - Ronald G. Petoch (1989). "Physico-biological characteristics". Conservation and Development in Irian Jaya: A Strategy for Resource Management. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. pp. 7–35. ISBN 978-90-04-08832-0.

- ^ Bsd e Drew et al. (2010), p. 46

- Piotr Naskreki (2005). Small majority. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. paragraph 38. ISBN 978-0-674-01915-7.

- WWF (2001). "Tropical rainforests of the Maldives - Lakshadweep - Chagos Archipelago (IM0125)". Terrestrial ecoregions

. National Geographic. Retrieved April 15, 2009. - Drew et al (2010), p. 49

- ^ abcde Fletcher (1993), p. 644

- ^ B s d e e by Peter Greenaway (2003). "Terrestrial adaptations in Anomura (Crustacea: Decapoda)". Memoirs of the Victoria Museum

.

60

(1): 13–26. DOI: 10.24199/j.mmv.2003.60.3. - ^ ab "Coconut crab (Birgus latro)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2015-11-10. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑

J. W. Harms (1932).

" Birgus latro

L. als Landkrebs und seine Beziehungen zu den Coenobiten."

Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie

(in German).

140

: 167–290. - W. J. Fletcher; I. W. Brown; DR Fielder; A. Obed (1991). Characteristics of molting and growth

. pp. 35–60. In: Brown and Fielder (1991) - V. Storch; W. Welsh (1984). "Electron microscopic observations of the lungs of the coconut crab, Birgus latro

(L.) (Crustacea, Decapoda)".

Zoologischer Anzeiger

.

212

(1–2): 73–84. - ^ a b K. A. Farrelly; P. Greenway (2005). "Morphology and vasculature of the respiratory organs of terrestrial hermit crabs ( Coenobita

and

Birgus

): gills, branchiostegal lungs and ventral lungs".

Structure and development of arthropods

.

34

(1):63–87. DOI: 10.1016/j.asd.2004.11.002. - ^ ab Warren J. Gross (1955). "Aspects of osmotic and ionic regulation in terrestrial crabs". American naturalist

.

89

(847): 205–222. DOI: 10.1086/281884. JSTOR 2458622. S2CID 84339914. - ^ abc Bill S. Hansson; Steffen Harch; Markus Knaden; Marcus Stensmire (2010). "Neural and behavioral basis of chemical communication in terrestrial crustaceans". In Thomas Breithaupt; Martin Thiel (ed.). Chemical communication in crustaceans

. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 149–173. DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-77101-4_8. ISBN 978-0-387-77100-7. - Marcus S. Stensmire; Suzanne Erland; Eric Hallberg; Rita Wallen; Peter Greenway; Bill S. Hansson (2005). "Insect-like olfactory adaptations in the terrestrial giant robber crab" (PDF). Current Biology

.

15

(2): 116–121. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.069. PMID 15668166. S2CID 9169832. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2009. - Jacob Krieger; Renate E. Sandeman; David S. Sandeman; Bill S. Hansson; Steffen Harch (2010). "Brain architecture of the largest living terrestrial arthropod, the giant robber crab Birgus latro (Crustacea, Anomura, Coenobitidae): evidence for a prominent central olfactory pathway?" . Frontiers of Zoology

.

7

(25): 25. DOI: 10.1186/1742-9994-7-25. PMC 2945339. PMID 20831795. - Taku Sato; Kenzo Yoseda (2008). "Breeding season and maturity size of female coconut crab Birgus latro

on Hatoma Island, southern Japan."

Fishery

.

74

(6):1277–1282. DOI: 10.1111/j.1444-2906.2008.01652.x. S2CID 23485944. - C. C. Tudge (1991). "Spermatophore diversity within and among the hermit crab families, Coenobitidae, Diogenidae and Paguridae (Paguroidae, Anomura, Decapoda)". Biological Bulletin

.

181

(2):238–247. DOI: 10.2307/1542095. JSTOR 1542095. PMID 29304643. - ^ abc K. Schiller; DR Fielder; I. W. Brown; A. Obed (1991). Reproduction, early life history and recruitment

. pp. 13–34. In: Brown and Fielder (1991) - Taku Sato; Kenzo Yoseda (2009). "Egg extrusion site of the coconut crab Birgus latro: direct observation of terrestrial animal egg extrusion" (PDF). Marine Biodiversity Records

.

Marine Biological Association. 2

: e37. DOI: 10.1017/S1755267209000426. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. - ^ a b Fletcher (1993), p. 656

- ↑

Fang-Lin Wang;

Hwey-Lian Hsieh; Chang-Po Chen (2007). "Larval growth of the coconut crab Birgus latro with a discussion of the mode of development of terrestrial hermit crabs". Journal of Crustacean Biology

.

27

(4): 616–625. DOI: 10.1651/S-2797.1. - ES Reese; R. A. Kinsey (1968). "Larval development of the coconut crab or robber crab Birgus latro

(L.) in laboratory conditions (Anomura, Paguridae)".

Crustaceans

. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. Suppl 2(2):117–144. ISBN 978-90-04-00418-4. JSTOR 25027392. - Fletcher (1993), p. 648

- ^ a b a Hartnoll (1988), p. 16

- S. Lavery; D. R. Fielder (1991). "Genetic characteristics". Project Overview and Literature Review

. pp. 87–98. - Peter T. Green; Dennis J. O'Dowd; PS Lake (2008). "Recruitment Dynamics in a Tropical Forest Seedling Community: The Context-Independent Impact of Key Consumer." Oecologia

.

156

(2):373–385. Bibcode: 2008Oecol.156..373G. DOI: 10.1007/s00442-008-0992-3. PMID 18320231. S2CID 13104029. - Jump up

↑ J. Bowler (1999).

"The robber crab Birgus latro on Arid Island, Seychelles" (PDF). Phelsuma

.

7

: 56–58. - Michael J. Samway; Peter M. Hitchins; Orti Burquin; Jock Henwood (2010). David J. W. Lane (ed.). "Tropical Island Restoration: Cousin Island, Seychelles." Biodiversity and Conservation

.

19

(2):425–434. doi:10.1007/s10531-008-9524-Z. HDL: 10019.1/9960. S2CID 25842499. - International Union for Conservation of Nature (1992). "United Kingdom, British Indian Ocean Territory". Afrotropical

.

Protected areas of the world: a review of national systems. 3

. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. pp. 323–325. ISBN 978-2-8317-0092-2. - ^ abcde e Thomas H. Streets (1877). "Some Information on the Natural History of the Fanning Island Group". American naturalist

.

11

(2): 65–72. DOI: 10.1086/271824. JSTOR 2448050. - ^ a b Joan E. Wild; Stuart M. Linton; Peter Greenaway (2004). "Dietary assimilation and digestive strategy of the omnivorous anomuran crab Birgus latro

(Coenobitidae)".

Journal of Comparative Physiology

B.

174

(4):299–308. DOI: 10.1007/s00360-004-0415-7. PMID 14760503. S2CID 31424768. - ^ abc Drew et al (2010), p. 53

- ↑

Peter Greenaway (2001).

"Sodium and water balance in free-ranging robber crabs, Birgus latro

(Anomura: Coenobitidae)."

Journal of Crustacean Biology

.

21

(2): 317–327. DOI: 10.1651/0278-0372(2001)021[0317:SAWBIF]2.0.CO; 2. JSTOR 1549783. - Kurt Kessler (2005). "Observation of predation by the coconut crab Birgus latro

(Linnaeus, 1767) on the Polynesian rat

Rattus exulans

(Peale, 1848)."

Crustaceans

.

78

(6):761–762. DOI: 10.1163/156854005774353485. - Buhler, Jake (November 9, 2017). "Giant Coconut Crab Sneaks Up on Sleeping Bird and Kills It". New scientist

. Retrieved November 10, 2022. - Anonymous (n.d.). "Coconut crabs (Birgus latro L.)" (PDF). University of Hawaii. pp. 1–6. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- Maurice Burton; Robert Burton (2002). "Robber Crab". International Wildlife Encyclopedia. 16

(3rd ed.). Marshall Cavendish. pp. 2186 -2187. ISBN 978-0-7614-7282-7. - Holger Rumpff (1986). Freilanduntersuchungen zur Ethologie, Ökologie und Populationsbiologie des Palmendiebes,

Birgus latro

L. (Paguridea, Crustacea, Decapoda), on Christmas Island (Indian Ocean)

[

Field studies on the ethology, ecology and population biology of the coconut crab,

Birgus

latroa L. (Paguridea, Crustacea, Decapoda) , Crustacea, Decapoda) on Christmas Island (Indian Ocean)

] (doctoral dissertation) (in German). Münster, Germany: Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster. Cited in Drew et al. (2010). - Dorothy E. Bliss (1968). "Transition from water to land in decapod crustaceans". American zoologist

.

8

(3): 355–392. DOI: 10.1093/ICB/8.3.355. JSTOR 3881398. - Hartnoll (1988), p. 18

- ^ a b Walcott (1988), p. 91

- S. S. Deshpande (2002). "Seafood Toxins and Poisoning". Handbook of Food Toxicology

.

Food Science and Technology. 119

. New York, New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 687–754. ISBN 978-0-8247-4390-1. - C. Maillaud; S. Lefebvre; K. Sebat; Y. Bargil; P. Cabalion; M. Chese; E. Khnavia; M. Noor; F. Durand (2010). "Double fatal poisoning by coconut crab ( Birgus latro

L.)."

Toxicon

.

55

(1):81–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.06.034. PMID 19591858. - Linda Orlando. “A giant spider that can crack a coconut? No, it's a crab! . Buzz. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- Stephen S. Amesbury (1980). "Biological studies of the coconut crab (Birgus latro) in the Mariana Islands" (PDF). Technical report from the University of Guam

.

17

: 1–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2011. - Fletcher (1993), p. 643

- Taku Sato; Kenzo Yoseda; Osamu Abe; Takuro Shibuno (2008). "Relationships between male maturity, sperm count and spermatophore size in the coconut crab Birgus latro on Hatoma Island, southern Japan". Journal of Crustacean Biology

.

28

(4):663–668. DOI: 10.1651/07-2966.1. - Kurt K. Kessler (2006). "Management implications of a coconut crab (Birgus latro) removal study on Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands" (PDF). Micronesica

.

39

(1): 31–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2012. - "Tuvalu Funafuti Nature Reserve". Ministry of Communications, Transport and Tourism - Government of Tuvalu. Archived from the original on 2011-11-02. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Jump up

↑ Alcock, A. W. (1898).

"A Summary of the Deep Sea Zoological Work of a Royal Indian Naval Service Ship Explorer from 1884 to 1897". Scientific Memoirs of Indian Army Medical Officers

.

11

: 45–109. - ^ I. W.

Brown;

D. R. Fielder (1991). Project Overview and Literature Review

. pp. 1–11.B: Brown and Fielder (1991) - ↑

Carl Linnaeus (1767). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae (in Latin). Tomus 1, Pars 2 (12th ed.). Stockholm, Sweden: Lavrentiy Salvius. item 1049. - Elena Menta (2008). "Review". In Elena Mente (ed.). Reproductive biology of crustaceans: case studies of decapod crustaceans

. Scientific publishing houses. paragraph 38. ISBN 978-1-57808-529-3. - "Wildlife of Okinawa". CNN Travel

. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

Bibliography[edit]

- I. W. Brown; D. R. Fielder, ed. (1991). Coconut crab: aspects of the biology and ecology

of Birgus latro

in the Republic of Vanuatu

.

ACIAR monograph. 8

. Canberra, Australia: Australian Center for International Agricultural Research. ISBN 978-1-86320-054-7. Available in PDF: pp. I–x, 1–35, pp. 36–82, pp. 83–128 - M. M. Drew; S. Hartsch; M. Stensmire; S. Erland; B.S. Hansson (2010). "A review of the biology and ecology of the robber crab, Birgus latro

(Linnaeus, 1767) (Anomura: Coenobitidae)".

Zoologischer Anzeiger

.

249

(1):45–67. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcz.2010.03.001. - Warwick J. Fletcher (1993). "Coconut Crabs". In Andrew Wright; Lance Hill (ed.). South Pacific Coastal Marine Resources: Information for Fisheries Development and Management

. Suva, Fiji: International Ocean Development Centre. pp. 643–681. ISBN 978-982-02-0082-1. - Richard Hartnoll (1988). "Evolution, systematics and geographical distribution". In Warren W. Burggren; Brian Robert McMahon (ed.). Biology of Land Crabs

. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–54. ISBN 978-0-521-30690-4. - Thomas G. Walcott (1988). "Ecology". In Warren W. Burggren; Brian Robert McMahon (ed.). Biology of Land Crabs

. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–96. ISBN 978-0-521-30690-4.

Appearance and features

Photo: What a palm thief looks like

The palm thief is a very large crayfish: it grows up to 40 cm and weighs up to 3.5-4 kg. Five pairs of legs grow on its cephalothorax. The front one is larger than the others, having powerful claws: it is noteworthy that they differ in size - the left one is much larger.

The next two pairs of legs are also powerful, thanks to them this crayfish can climb trees. The fourth pair is smaller in size than the previous ones, and the fifth is the smallest. Thanks to this, young crayfish can squeeze into other people's shells, which protect them from behind.

It is precisely because the last two pairs of legs are poorly developed that it is easiest to establish that the palm thief should be classified as a hermit crab, and not at all a crab, for which this is not typical. But the front pair is well developed: with the help of the claws on it, the palm thief is able to drag objects ten times heavier than himself, and they can also become a dangerous weapon.

Since this cancer has a well-developed exoskeleton and full lungs, it lives on land. It is curious that his lungs consist of the same tissues as the gills, but they absorb oxygen from the air. At the same time, it also has gills, but they are underdeveloped and do not allow it to live in the sea. Although he begins his life there, but after he grows up, he loses the ability to swim.

The palm thief makes an impression with its appearance: it is very large, the claws especially stand out, because of which this crayfish looks menacing and very much like a crab. But it does not pose a danger to a person unless the person decides to attack: then with these claws the palm thief can really inflict a wound.

Interesting Facts

- The palm thief is the largest terrestrial crustacean on land.

- The shell has an unusual red or sky blue color. The color scheme is represented by bright red, turquoise, and blue.

- They are hermits.

- Possesses an extremely strong sense of smell. Brain activity is 40% dependent on information coming from olfactory receptors.

- The claw has an incredible compressive force. No other animal on earth has such an ability. It has the most powerful pair of claws among all crustaceans.

- The coconut crab was first described by legendary biologist Charles Darwin.

- They prefer a solitary lifestyle.

- Their meat is considered a great delicacy.

- They can pose a great danger to both humans and representatives of the animal world.

- Once in the water, an adult crab can drown.

- Over the past half century, crab numbers have declined by 30%. Significant legislative measures are needed in the habitats of crayfish, which will increase their population and regulate catching. Pregnant females and large adults especially need protection.

Where does the palm thief live?

Photo: Palm thief crab

Their range is quite wide, but they live mostly on islands of modest size. Therefore, although they are scattered from the coast of Africa in the west and almost to South America in the east, the land area on which they can live is not so large.

The main islands where you can meet the palm thief:

- Zanzibar;

- eastern Java;

- Sulawesi;

- Bali;

- Timor;

- Philippine Islands;

- Hainan;

- Western Oceania.

The small Christmas Island is known as the place most densely populated by these crayfish: they can be found there at almost every step. As can be seen from the list as a whole, they prefer warm tropical islands, and even in the subtropical zone they are practically not found.

Although they also settle on large islands, like Hainan or Sulawesi, they prefer small ones, located next to large ones. For example, in New Guinea, if they can be found, it is very rare, on the small islands lying to the north of it - very often. It's the same with Madagascar.

They generally do not like to live near people, and the more developed the island becomes, the fewer palm thieves remain there. Small, preferably uninhabited islands suit them best. They make their burrows near the coastline, in coral rock or rock crevices.

Interesting fact: These crayfish are often called coconut crabs. This name arose due to the fact that it was previously believed that they climb palm trees in order to cut coconuts and feast on them. But this is not so: they can only look for already fallen coconuts.

Save the coconut crab

- Support mitigation of the climate crisis and help fight global warming, which threatens to destroy coconut crab habitat.

- While traveling, spend time in protected areas such as Christmas Island National Park in Australia, home to the world's largest population of coconut crabs.

- Reduce the amount of plastic waste ending up in the ocean and help lead beach cleanups to keep our oceans healthy.

Treehugger

Gulnara Dadabaeva

Science writer, professional zoologist and educator with over 10 years of experience working with students, scientists and government experts. Freelance author of the website “Knowledge is Light”.

What does the palm thief eat?

Photo: Palm thief in nature

Its menu is very diverse and includes both plants and living organisms, and carrion.

Most often he eats:

- contents of coconuts;

- pandan fruits;

- crustaceans;

- reptiles;

- rodents and other small animals.

He doesn’t care what living creatures he eats, as long as they are not poisonous. He catches any small prey that is not fast enough to get away from him, and not careful enough to avoid being caught by him. Although the main sense that helps him when hunting is smell.

He is able to smell prey at a great distance, up to several kilometers for things that are especially attractive and fragrant to him - namely, ripe fruits and meat. When residents of tropical islands told scientists about how good a sense of smell these crayfish have, they thought that they were exaggerating, but experiments confirmed this information: the baits attracted the attention of palm thieves at a distance of kilometers, and they unmistakably gravitated towards them!

Owners of such a phenomenal sense of smell are definitely not in danger of dying from hunger, especially since the coconut thief is not picky, he can easily eat not only ordinary carrion, but even detritus, that is, long-decomposed remains and various secretions of living organisms. But he still prefers to eat coconuts. Finds fallen ones and, if they are at least partially split, tries to break them with the help of claws, which sometimes takes a lot of time. It is not capable of breaking the shell of a whole coconut with its claws - previously it was believed that they could do this, but the information was not confirmed.

They often drag prey closer to the nest to break the shell or eat it next time. It is not at all difficult for them to lift a coconut; they can even drag weights of several tens of kilograms. When Europeans first saw them, they were so impressed by the claws that they claimed that palm thieves could even hunt goats and sheep. This is not true, but they are quite capable of catching birds and lizards. They also eat only newly born turtles and rats. Although for the most part they still prefer not to do this, but to eat what is already available: ripe fruits and carrion that have fallen to the ground.

They eat coconuts

It's no surprise that coconuts make up a significant portion of the coconut crab's diet. Thanks to their curved legs and inward grip, they can climb palm trees and crack coconuts with ease with their strong claws. However, that's not all they eat, as they have also been observed hunting animals such as rats, migratory seabirds, and even each other. In the Chagos Archipelago, Earth's largest coral atoll, palm thieves launched a direct attack by sneaking up and capturing an adult red-footed booby under the cover of darkness. ()

Features of character and lifestyle

Photo: Cancer palm thief

You can rarely see them during the day, since they go out at night in search of food. In the light of the sun they prefer to stay in shelter. This could be a hole dug by the animal itself, or a natural shelter. The inside of their homes is lined with coconut fiber and other plant materials, which allow them to maintain the high humidity they need for a comfortable life. The crayfish always covers the entrance to its home with its claw; this is also necessary so that it remains moist.

Despite such a love for moisture, they do not live in water, although they try to settle nearby. They can often approach its very edge and become slightly moist. Young crayfish settle in shells left by other mollusks, but then they grow out of them and are no longer used.

Palm thieves often climb trees. They do this quite deftly, with the help of the second and third pairs of limbs, but sometimes they can fall - however, this is no big deal for them, they can easily survive a fall from a height of up to 5 meters. If they move backwards on the ground, then they descend from the trees head first.

They spend most of the night either on the ground, eating the prey they find, less often hunting, or near the water, and in the late evening and early morning they can be found in the trees - for some reason they really like to climb there. They live quite a long time: they can grow up to 40 years, and then they do not die immediately - individuals are known that have lived up to 60 years.

Social structure and reproduction

Photo: Palm thief crab

Palm thieves live alone and are found only during the breeding season: it begins in June and lasts until the end of August. After a long courtship, the crayfish mate. A few months later, the female waits for good weather and goes to the sea. In shallow water, she enters the water and releases her eggs. Sometimes the water picks them up and carries them away, in other cases the female waits in the water for hours until the larvae hatch from the eggs. She doesn’t go far, because if a wave carries her away, she will simply die in the sea.

Laying is done during high tide so that the eggs do not wash back to the shore, where the larvae die. If everything went well, many larvae are born, which are still in no way similar to the adult palm thief. Over the next 3-4 weeks they float on the surface of the water, noticeably growing and changing. After this, small crustaceans sink to the bottom of the reservoir and crawl along it for some time, trying to find a home. The faster this can be done, the greater the chances of survival, because they are still completely defenseless, especially their abdomen.

The house can be an empty shell or a small nut shell. At this time, they are very similar to hermit crabs in appearance and behavior, and constantly remain in the water. But the lungs gradually develop, so that over time, young crayfish come to land - some earlier, some later. Initially they also find a shell there, but at the same time their abdomen becomes harder and harder, so that over time the need for it disappears, and they discard it.

As they grow, they molt regularly - they form a new exoskeleton, and they eat the old one. So over time they turn into adult crayfish, changing dramatically. Growth is slow: they reach sexual maturity only by the age of 5, and even by this age they are still small - about 10 cm.

How do small crabs develop?

During this period of life, with a shell on their back, the crabs closely resemble hermit crabs and carry a house until the abdomen begins to gradually harden. Further in the development of the young crab, a period of molting occurs, during which the arthropod repeatedly sheds its shell.

The final stage of “growing up” of a young crab is tucking its tail under its abdomen, which provides a kind of protective measure against possible damage. As they grow, crabs gradually lose the ability to breathe underwater and soon finally move to their main habitat - on land.

Coconut crabs reach maturity approximately 5 years after hatching; They reach their maximum size at about 40 years of age.

Natural enemies of palm thieves

Photo: Palm Thief

There are no specialized predators for which palm thieves are their main prey. They are too large, well protected and can even be dangerous to be hunted constantly. But this does not mean that nothing threatens them: large cats and, more often, birds can catch and eat them.

But only a large bird can kill such a cancer; not every tropical island has such creatures. Basically, they threaten young individuals that have not even grown to half their maximum size - no more than 15 cm. They can be caught by birds of prey such as kestrel, kite, eagle, and so on.

There are much more threats to the larvae: they can become food for almost any aquatic animal that feeds on plankton. These are mainly fish and marine mammals. They eat most of the larvae, and only a few of them survive to reach land.

We must not forget about humans: despite the fact that palm thieves try to settle on as quiet and uninhabited islands as possible, they often find themselves victims of people. This is all because of their tasty meat, and their large size does not play in their favor: they are easier to notice, and it is easier to catch one such crayfish than a dozen small ones.

Interesting fact: This cancer is known as the palm thief because it loves to sit on palm trees and steal everything that glitters. If he sees tableware, jewelry, or any metal in general, Cancer will definitely try to take it into his home.

Is it edible?

The thief is not only edible, but also incredibly tasty. Coconut crab meat has a similar taste to lobster and lobster meat and is also cooked. There is a myth that the meat has a coconut flavor due to the nature of its nutrition, this is not true, the tender flesh of the palm thief does not have a nutty taste.

Palm crab meat is a real delicacy and many gourmets will deliberately interfere with its habitat to taste it. In addition to its amazing taste, the inhabitant of the tropics is a powerful aphrodisiac, causing sexual desire, because of this, the hunt for crayfish has increased greatly and the authorities of some regions have limited fishing.

In restaurants in Guinea, individuals do not eat meat. On the island of Saipan you can catch representatives with a hard shell up to 4 centimeters.

In all habitats of the thief, hunting them during the breeding season is prohibited.